August 15th, 1995, Blind Melon released their second album, Soup, through Capitol Records. In hindsight, Blind Melon’s sophomore album was audacious, unique, mature, experimental and strange. It was also maligned, misunderstood and maddening. Right from the outset, album opener “Hello, Goodbye” sets the band’s stall, as Shannon Hoon sings in a mock-vaudevillian voice against boozy New Orleans brass “I’m entering a frame bombarded by indecision, where a man like me can easily let the day get out of control, down this far in the Quarter.” As the horns fade, we’re flung into the pummeling one-two punch of “Galaxie” and “2×4.” It’s clear this is not the Blind Melon of the carefree smash hit “No Rain”

The story of Soup is inextricably linked to New Orleans. A city that has always been a beacon for wayward artists. The New Orleans of the mid-90s was filled with endless distractions, 24/7 parties, bars that never closed and anything you want, available at any time. By this time, Trent Reznor, Marilyn Manson, Greg Dulli, Johnny Thunders and Alex Chilton had fallen for its charms and had relocated there, and so too did Blind Melon.

After a monumental two-year world tour supporting their lightning bolt of a debut album, the band were ready to hunker down and work on the follow-up. Hundreds of days on the road made Blind Melon a tighter, more confident, and better band. The time away from home also mired the group in destructive indulgences, including the overuse of drugs. “We didn’t really think to ourselves, ‘Hey man, New Orleans is probably the worst place for us to be,'” says guitarist Christopher Thorn. “In the moment, it felt romantic and like exactly what we should be doing.”

The writing process for Soup differed from the collective experience of writing their quadruple-platinum self-titled debut in North Carolina. With band members demoing and recording songs and ideas alone and bringing them to the group, many songs were almost fully formed before the band got hold of them, which may account for the shift in sound and feel between the debut and Soup. The debut bristles with a joyous energy and a passionate, naïve enthusiasm. The follow-up is darker, more robust, heavier, peculiar, funny, heart-breaking and bizarre.

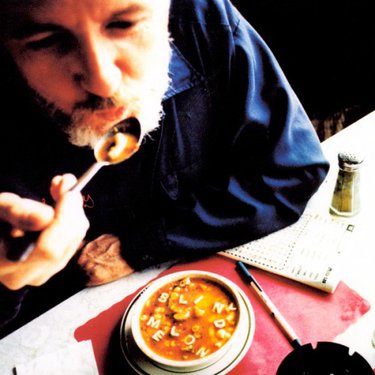

Producer Andy Wallace (who also appears on the album’s front cover, eating a bowl of alphabet soup) set the band up in Kingsway, a mansion-turned-recording studio owned by producer Daniel Lanois on the edge of the French Quarter. Initially, the recording went well; the band were sharp, and the songs flowed fast.

Before long, though, the city’s party atmosphere began to take over the sessions. Drug dealers became common fixtures, and Hoon sightings became rare. “You only got Shannon for so much time,” recalls Thorn. “I don’t know how Andy even finished that record for us. If you’re lucky, you got Shannon for a few hours a day.” And even then, what they got wasn’t always pretty…”

It wasn’t just Hoon running amok; most of the band were in a frenzied state. In many respects, that wild atmosphere bled into the creation of the album; the enormous success of the band’s debut meant they were free of outside interference; they were calling their shots. Guitarist Christopher Thorn said, “We didn’t have to answer to anybody and felt like we could do whatever we wanted. That’s a great way to make art when you’re not making decisions in fear.”

Guitarist Rogers Stevens reflects, “The arrangements were kind of unconventional; the things we were listening to at the time weren’t the most accessible.”

By Soup’s release in August of 1995, the year had already delivered landmark alternative rock albums like Smashing Pumpkins, Mellon Collie and The Infinite Sadness, Mad Season’s Above and Foo Fighters debut, among many more. These were Blind Melon’s contemporaries, and expectations were high for their new offering. But even in the super diverse, anything-goes era of the ’90s alternative rock landscape, Soup struggled to be understood.

MTV buried the videos for “Galaxie” and “Toes Across the Floor.” Radio was unimpressed, too. “Galaxie” briefly reached No. 8 on the Billboard Modern Rock chart, but “Toes Across the Floor” didn’t chart at all. Possibly the biggest blow was a scathing review by Rolling Stone hack Ted Drozdowski, who gave the album a ridiculous one-and-a-half-star review and ended his write-up with the statement, “With such slight fare to offer, and no kid in a bee suit. Soup puts Blind Melon in hot water.”

Unlike today, in 1995, Rolling Stone was still king makers, and the band took this review hard. “It fucking devastated us,” says Thorn. “We thought we made this amazing record, and we thought everyone would be super proud of us for not trying to repeat ‘No Rain’ again. We thought we had made Exile on Main Street. Then the review comes out, and someone says, ‘Hey, what you made, that you were so proud of, is absolute shit.'”

Then, just two months after the album was released, tragedy hit like a tsunami. Shannon Hoon was found dead in the band’s tour bus, after a disappointing performance at Numbers Club in Houston on October 20th. Having been clean for some time, Hoon went on an all-night drug binge. The next day, Blind Melon was scheduled to play a show in New Orleans at Tipitina’s. The band’s sound engineer, Lyle Eaves, went to the tour bus to awaken Hoon for a sound check, but Hoon was unresponsive. An ambulance arrived, and Hoon was pronounced dead at the scene at the age of 28. His death was attributed to a cocaine overdose.

“I never processed how much pain was in the lyrics on Soup until after Shannon passed away,” Thorn says. “He was telling everybody, ‘Hey man, this is not good. I’m kind of fucked up; I might be going out.”

Another odd fact remains hard to understand to this day. Though band members had zero interest in sales metrics after their friend’s tragic exit, even Hoon’s passing couldn’t bring attention to this album. The public’s outpouring of grief when a larger-than-life frontman or frontwoman dies is predictable. What follows is the usual media saturation and sales spikes. But for Blind Melon, there would be no posthumous “bump.” The video for Soup’s second single, “Toes Across The Floor,” reached MTV a couple of days before Hoon’s death. Instead of airing it as a tribute to the now-defunct band, the network brushed the clip aside.

Capitol Records followed a similar path, distancing itself from all things Blind Melon in the wake of the news. “After Shannon died, not one person from that record company ever called me to offer their sympathies,” Thorn says. “They didn’t even contribute to the fund we set up for Shannon’s baby daughter, Nico. It was like we disappeared.”

The truth is, Soup is a ragged masterpiece. It was criminally overlooked and discarded at the time of its release. And like all great art, it has only improved with time and perspective. It’s an album that could have only been conceived in the ’90s. It was a time when creativity and individuality in rock music were cherished and encouraged. Tracks like the barn burning “Galaxie” and “2×4.” The heavy blues of “Vernie”, a song Shannon penned as a tribute to his grandmother—the foot-stompin’ acoustic folk of “Skinned” replete with a wicked Kazoo. The transcendental glide of “Toes Across The Floor” is revelatory. “Walk” is another more reflective acoustic workout followed by the punk energy meets Zappa out-thereness of Dumptruck.

The southern groove of “Wilt” morphs into a Beatles-esque type wig-out. “The Duke” is an audible LSD trip, a slide through a technicolour soundscape. “St Andrews Fall” is prime Blind Melon, unique guitar, bass and drum interplay, with a vast chorus hook. “New Life,” written when Hoon learned his girlfriend, Lisa Sinha, was pregnant, contains some of his warmest melodies and lyrics. “Mouthful Of Cavities” is absolute perfection and is one of Blind Melon’s finest songs. Essentially a duet, the song features the evocative voice of Jenna Kraus, who weaves beautifully around Hoon’s vocal. “Lemonade” is a rawkus rocker that stumbles over itself while never missing a step.

Musically, the album’s hidden track starts not dissimilar to something Tom Waits may have added to his stunning album Mule Variations (released four years after Soup, in 1999), but rather than Waits rough baritone, we get Hoon speaking in tongues and channelling the genius of Mary Margaret O’Hara’s hiccupped vocal delivery on her 1988 masterpiece “Miss America.”

Blind Melon shifted through sounds, styles and genres on Soup in a way few bands could even dream of. And while stretching themselves artistically and creatively, they still delivered a superbly coherent album. The history of music is littered with many stories of critics and audiences “not getting” a band’s sudden shift in artistic vision. It was plain to see from the very moment Blind Melon arrived they were not followers. They carved their path. Their debut stood out like a glorious, throbbing sore thumb on release, so why was it such a shock when they released another strange, beautiful and awe-inspiring album, that was unlike anything around it..?

In recent years, Soup has gained a diehard following. And rightly so. It can be a challenging listen, but its rewards are worth the effort. Soup is Shannon Hoon’s final artistic statement, which he can be proud of. Where Hoon and Blind Melon would have gone after this is anybody’s guess. Soup would have been quite the act to follow.

“I would really like people to remember how amazing Shannon was; that would be the most gratifying thing,” guitarist Rogers Stevens says of Soup’s legacy. “On the surface, he could play the clown, but the guy was deep, smart, and super talented. And he didn’t get a chance to put all that out there. He had a lot more to offer.”

Soup is uncategorizable and utterly brilliant, much like Hoon himself.

Essential…!