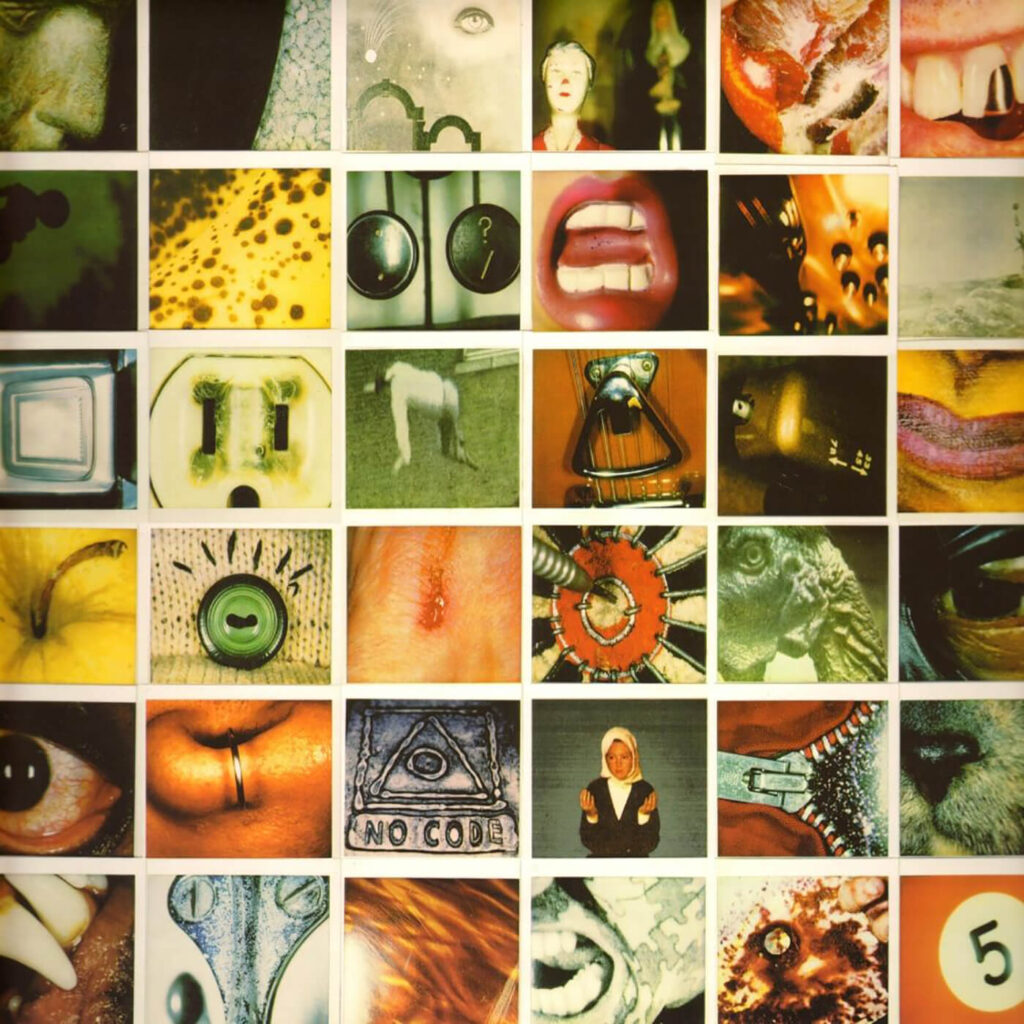

August 27th, 1996, Pearl Jam released their fourth album, No Code, on Epic Records. So much had changed in the five years (to the day) since Pearl Jam released their debut album, Ten. The ever-revolving drum stool position had changed again with Jack Irons’s introduction. Irons, former Red Hot Chili Peppers and Eleven stickman, was Pearl Jam’s fourth drummer in six years. He was a natural fit, a known entity, and an old friend, having been instrumental in Pearl Jam’s formation. In 1990, Irons and Vedder were close friends living in San Diego, California. It was he who passed on a demo tape of new songs by former Mother Love Bone members Stone Gossard and Jeff Ament to the then-unknown Eddie Vedder. The rest, as they say, is history.

After Pearl Jam’s sudden success with Ten in 1991, Vedder’s first response was to open himself up. He’d write back when fans sent letters about his lyrics, questioning him about depression and alienation. But in time, the band’s enormous, snowballing fame meant the letters turned into an avalanche. Then fans started coming to his house. A girl who believed Vedder was Jesus and had fathered her two sons by raping her almost killed herself by ramming her car into the wall of his house at 50mph.

“One of the reasons you’re protecting yourself is because you’ve been forthcoming with your emotions,” Vedder says. “So you have to build a wall. And now people are driving into the wall. That’s what fucks with your head. I felt like my brain was a whore, and I was getting mindfucked.” He continued, “I was almost overwhelmed by it all. I had this house, not a giant house, but three or four nice rooms and a jukebox. And it had this laundry room, and I would sit in there with an ashtray I trusted. It was like the world couldn’t get me in the laundry room.”

More and more the band and Vedder in particular became withdrawn. The contrast between Vedder on-stage circa 1992 and Vedder on-stage circa 1995 had become stark. His demeanour spoke volumes of how his and the band’s internal word was playing out. The once carefree, wide open, crowd surfing, stage scaffolding climbing Eddie Vedder of the Ten era had slowly given way to a guarded, stationary, menacing, contorted figure, clutching his mic stand with unbridled passion.

The band’s conscious decision to step back from the spotlight after their rapid rise to mega-stardom, offered their fans the chance to follow them down the rabbit holes of their creativity or jump ship altogether. Many saw this stance as career suicide. This retraction began with their second album, 1993’s Vs., as the band refused to make promotional videos for any of the four singles released. At a time when MTV and the music video were the lifeblood of a band’s career, this was unheard of. And so it continued with their third album, 1994’s Vitalogy, the band this time refusing to conduct any interviews (but a select few they chose), make music videos or play ball in any way with the regular PR routes of the music industry machine.

Pearl Jam always attracted uninformed criticism from elitists who considered them “corporate rock” or, in some way, “sellouts.” But they did more than any band of their era to quell the insatiable feeding frenzy around the band. Nirvana, a band who are often pitted against Pearl Jam in the credibility stakes, had only one real protest against their spectacular rise to fame, which was to banish their biggest hit, “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, from their set list, with all other established forms of music industry PR being fair game. Pearl Jam slammed the door on every facet of the “game.”

Ultimately, there’s no right or wrong approach. Pearl Jam’s decisions were incredibly ballsy and spoke of their determination to stay true to themselves and not get eaten by a ruthless machine. It was a defiant punk rock move by a band many considered the antithesis of punk rock values. These decisions laid the foundations for the survival of Pearl Jam as a band and Vedder as their frontman.

Another event that alerted the whole world to celebrity life’s pitfalls was the suicide of Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain. The unrelenting pressure of fame and a crippling drug habit drove Cobain to the ultimate end, out of the Seattle big four that spearheaded the grunge alternative rock revolution of the early ’90s. Nirvana and Pearl Jam led the way in popularity, sales and attention. Kurt’s suicide only hardened Pearl Jam’s position and caused them to circle the wagons even tighter.

The band began work on No Code at the Chicago Recording Company studios in Chicago for a week in July 1995, followed by a week-long session in New Orleans, Louisiana, where the band recorded “Off He Goes”. The rest of the recording took place in the first half of 1996 in Seattle at Studio Litho, which guitarist Stone Gossard owns. Brendan O’Brien, who worked on Vs and Vitalogy, was again in the producer’s chair.

By all accounts, the band’s interpersonal relationships were not in a good place during recording. Bassist Jeff Ament was unaware that the band had started recording until three days into the sessions. Guitarist Mike McCready said, “I’m sure Jeff was pissed, but it was more about separating because nothing would get done if we played all together. We’d all just get pissed off at each other.” At one point, Ament even walked out of the recording sessions and considered quitting the band due to Eddie Vedder’s control of the creation process.

The adage, “Out of striff, comes great art,” may apply to No Code. The album opens with a first for Pearl Jam. Rather than hitting the listener out of the gate with a barnburner, as they did on previous albums (Once – Ten, Go – Vs, Last Exit – Vitalogy), We get “Sometimes,” a contemplative, chiming lullaby that floats the listener gently towards the furious waterfall that is second track “Hail, Hail.”

“Hail, Hail” is built around a classic Stone Gossard riff that acts as a musical bridge to Pearl Jam’s recent past. Sharing the same vital, aggressive attack that littered the more vitriolic tracks on Vs and Vitalogy, “Hail Hail” serves as a reminder that Pearl Jam can still rock like bastards. The third track and first single, “Who You Are,” is the point at which the listener must decide about this record. Credited musically to Gossard and Irons, the track is built out of a jam in which Irons’s drumbeat (“I’d been playing that pattern since I was eight”, Irons said) is built upon Gossard’s dissonant guitar part and Vedder’s electric sitar. Its vocal melody has a lullaby-like quality in its simplicity.

“Who You Are” sets the tone for how No Code will unfold. It’s a very different-sounding Pearl Jam to the band that brought us Ten, Vs and even Vitalogy. It’s the sound of a band pushing their boundaries and an insight into where the power dynamic and songwriting choices were shifting. “In My Tree” is built upon Jack Irons’s inventive, percussive drumming.

Vedder intones, “Up here in my tree, Newspapers meant enough to me, No more crowbars to my head, I’m trading stories with the leaves instead, Wave to all my friends, They don’t seem to notice me…” Vedder’s desire to retract from the limelight plays out over a looping, tribal rhythm with a distinctly “world music” feel.

“Smile” has the languid chug of prime Neil Young and Crazy Horse, complete with harmonica and a clipped guitar solo from Mike McCready. “Off He Goes” is a stunningly beautiful acoustic ballad filled with pathos. This stripped-bare serenade resembles Nebraska-era Bruce Springsteen. With “Habit”, Pearl Jam flipped the high octane switches and let rip, which is a welcome change of tone. The guitars rage with a metallic sheen as Vedder spits barely concealed, apoplectic rage into the mic against the drug abuse laying waste to the band’s Seattle contemporaries.

“Red Mosquito” is buoyed by Mike McCready’s fantastic slide guitar playing. It’s the first time on the album he’s allowed to stretch out and display his incendiary skills. Regarding McCready’s lead guitar work, Vedder said, “In the studio, he played that slide part with a Zippo lighter…an old Zippo lighter. It belonged to my grandpa, and afterwards, Mike asked if he could have it, and I said, ‘No..!” The song’s waltz time feel and heavy dynamics lead into the 62-second punk rock blast of “Lukin.”

“Lukin” is named after Matt Lukin, the erstwhile bass player for Pacific Northwest legends Melvins and Mudhoney, who is Vedder’s close friend. When Eddie needed to escape his stalker problem, he and his wife would sometimes hang out at Lukin’s place. Apparently, he kept his refrigerator well stocked, “Open the fridge; now I know life’s worth.” The song was purposefully kept very short because Matt Lukin used to tease Vedder about how long Pearl Jam songs were.

Mike McCready’s “Present Tense” starts with a gorgeously cinematic tone. Waves of atmosphere envelop the listener as Vedder’s lyrics look to make amends with his younger self and seek a newer, wiser direction; McCready’s writing and playing suggest a similar process is taking place within the whole band. The song builds and builds until the band’s introduction at the three-and-a-half-minute mark. From there, the song erupts similarly to the equally emotive outro of “Corduroy” from Vitalogy.

For “Mankind” guitarist Stone Gossard takes the lead vocal in a scathing put-down of imposter bands flooding the music scene, “You’ll be going out with radio, Going out with disco, going out like bacchanal…” The spoken word “I’m Open” lives up to its title, with delicate guitars dancing around Vedder’s lyrics about the loss of youthful innocence. The album ends on another contemplative note with “Around The Bend,” a folk ballad, unhurried and languid. It pretty much sums up where Pearl Jam was circa 1996.

With No Code, Pearl Jam did their best to shake off the shackles of their previous success and dive headlong into an unknown future. It’s arguably their most experimental album and paved the way for future albums like Binaural and Riot Act. Besides a few flashes of bombastic rock moments, it’s a more reflective and sombre affair. Pearl Jam is not a punk band per se, but in spirit and through their actions, they were more committed to the punk rock ethos than many actual punk bands. At its release, No Code split fans and critics straight down the middle. Many missed the exhilarating rush of Ten and Vs. Others embraced the new approach and path the band were now on.

Looking back, it’s hard not to admire the sheer force of will the band displayed in steering the ship in a new direction when everyone around was urging them to stay on course. But all agree that Vedder’s decision to withdraw from mega-stardom was crucial. This wasn’t just a panicked reaction to the stalker incidents but the result of pragmatic thinking. As other bands toppled around them, Vedder realised that carrying on as they had been doing would kill the group. Scaling down and setting their sights slightly lower could mean survival, even if it meant making some very “unpopular decisions.”

The album was a turning point in Pearl Jam’s career and opened up new paths for the future. It’s a brave statement that found its place more and more in the hearts of fans as time passed. And that’s the real beauty of No Code.