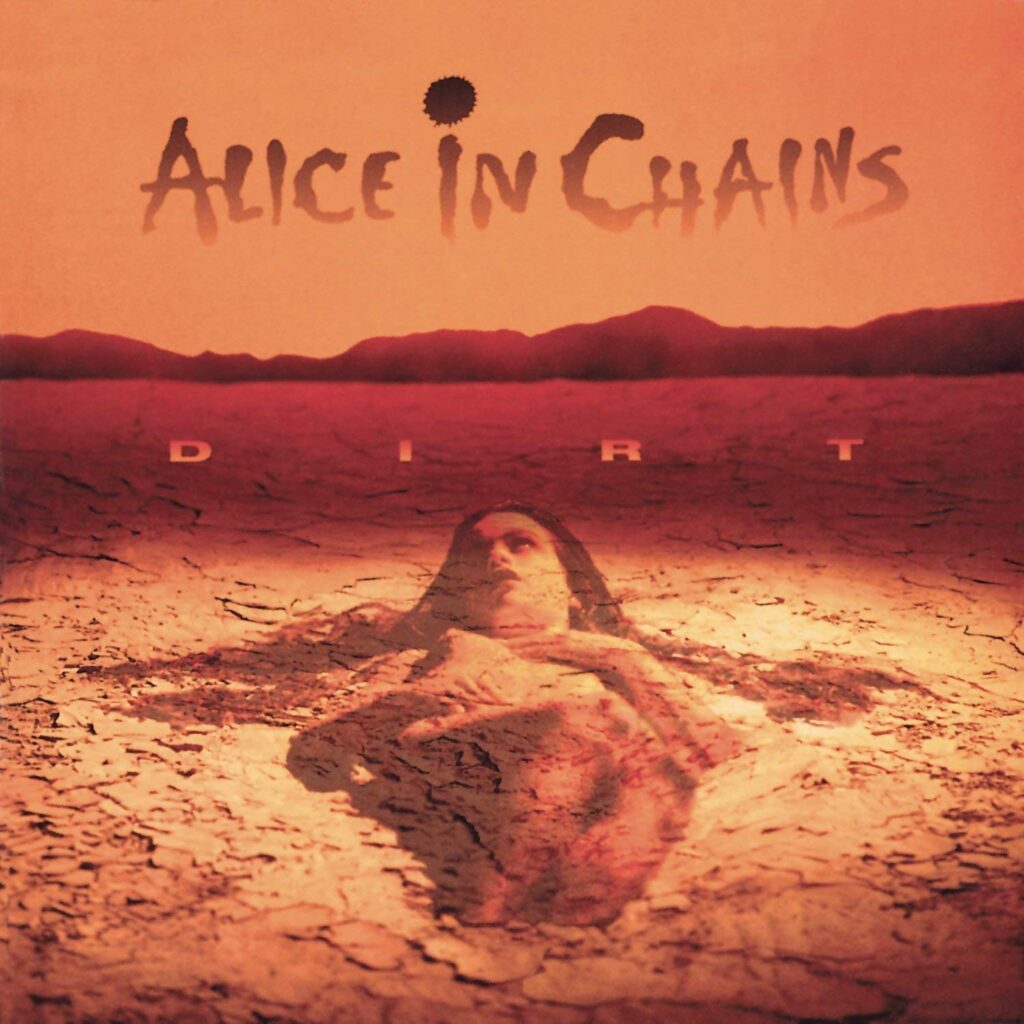

September 29th, 1992, Alice In Chains released their second studio album, Dirt, through Columbia Records. “By the time Facelift had come out, we were already working towards Dirt,” explained Alice In Chains drummer Sean Kinney in 2022. “Things were being written while we were touring Facelift, playing different versions of some of these new songs live and working them into what they ended up being.” Guitarist Jerry Cantrell added, “Things had taken off. We’d had a successful tour and campaign for Facelift; we were on tour for eighteen months. And during that time, I was always collecting ideas. Back then, it was a little handheld tape recorder or a little Tascam four-track you’d dump your ideas into. There were also jams during rehearsals and in dressing rooms and soundchecks. When we finished that tour, I had a lot of good ideas, and collectively, as a band, we had some interesting things going on.”

The dark spectre of drugs and heroin, in particular, loomed large over the Pacific Northwest music scene in the early ’90s. Seattle was ‘ground zero’ for the resurrection of heroin use in American cities, with overdose fatalities in the city increasing by 300% from 1986 to 1994. Heroin was imported from Mexico and flooded into Seattle through the city port, one of the largest in America, and anyone who had the will and enough money to partake did so.

Many bands used or were inspired by heroin’s bleak seduction. But no other band so blatantly addressed its dark spiral, lyrically and musically, like Alice In Chains. By early ’92, all of the band members were struggling with various substance and mental issues: Staley with heroin; Kinney and Starr with alcohol addiction; and Cantrell with substance abuse and clinical depression following the death of his Mother and close friend Andrew Wood of Mother Love Bone.

Despite the dark clouds, the band were on fire. Buoyed by the grunge explosion, their debut album, Facelift, released in August of 1990, was certified triple platinum for sales of over three million copies. By 1992, Alice In Chains was one of the biggest rock bands on the planet. The band decamped from Seattle to Los Angeles to work on Dirt – just as the infamous 1992 Los Angeles riots broke out following the acquittal of the police officers who had been filmed beating motorist Rodney King.

Jerry Cantrell recalled, “We came down to LA, started tracking the record, and that Rodney King verdict came down, the fucking town went up in flames. We were staying at the Oakwoods in Venice — so we had to come from Studio City to Venice while the whole city was in a riot. We called up Tom Araya from Slayer, went out to the desert and hung out there until the shit cooled down. We had to postpone recording until the riots fucking chilled out. That’s a moment tied to that record I’ll never forget.”

The recording of Dirt took place at Eldorado Recording Studio in Burbank and One-on-One Studios in Los Angeles, California, during the spring of 1992. The band had already recorded the song “Would?” with Rick Parashar at London Bridge Studio in Seattle. That song featured on the soundtrack of Cameron Crowe’s Seattle-based movie Singles. With the release of the Singles soundtrack in June of 1992, “Would?” became the first new material fans would hear from Dirt.

Before recording began, the band needed to do some pre-production, “We started in California, and we still had to buff some of the material into shape,” Cantrell recalled. “We needed to do a little bit more woodshedding. I remember we went out to some studio, which was like a converted barn, out in Malibu. It belonged to Mick Fleetwood, which we all thought was pretty cool because we’re big Fleetwood Mac fans. We hung out there for about two weeks and fleshed out some ideas. One song in particular, ‘Rain When I Die,’ I remember we sewed that up in that room.”

Staley had recently checked out of rehab but had returned to using heroin by the time recording sessions were underway in Los Angeles. This caused significant tension, especially between Staley and producer Dave Jerden, “Layne got all mad at me during the Dirt sessions,” Jerden recalled, “My job as a producer was to produce the record. I’m not getting paid to be Layne’s friend.”

“‘Dirt’ was never a drug concept album,” said Sean Kinney in 2022, “And Layne wasn’t a dick. He wasn’t tormented but instead witty, funny and generous. And he and Ann Wilson were the two loudest projecting singers I’ve worked with in my life. Layne was great at everything except for being a rock star. Doom and gloom may be a stigma affecting perceptions of ‘Dirt,’ but in reality, part of that album talks about how cool it all is, then five songs later tells you how drugs suck. Most of our music is about persevering and overcoming. But all of us had similar situations to Layne at that time. But it’s bittersweet. There are great memories, but I don’t get to talk to Mike Starr and Layne about how fucking weird it all is years later to have ‘Dirt’ re-chart.”

Dirt sounds incredible; the production is crisp, warm, and huge. Having worked with the band on their debut Facelift, Deve Jerden knew how to coax the best performances from each member. He also got a little inside knowledge about the studio they used from the previous band to record there. “We recorded it at One On One, where Metallica did their “Black” album,” recalls Jerden, “Lars Ulrich told me Metallica had used this 31-inch woofer for the kick drum. I rented a PA system and put the kick drum, toms and snare through this woofer, plus these huge side monitors that went into the room, making the drums sound like artillery going off. I credit Lars with turning me on to that room.”

Dirt opens with the ferocious “Them Bones” at a mere two minutes and thirty seconds; it packs a savage punch. Jerry Cantrell’s thick palm-muted chords ascend aggressively. Each chug is laced with chromatic dissonance as Mike Starr’s bass underpins the changes. Sean Kinney’s drums sound enormous and heavy. Layne screams a death howl on the downbeat of each turnaround. It’s a startling introduction to the album.

“Dam That River” keeps the intensity at a fever pitch. It’s pummelling directness is exhilarating. Layne spits venom, “I broke you in the canyon, I drowned you in the lake, You a snake that I would trample, Only thing I’d not embrace.” It’s another short, sharp shock at three minutes and ten seconds.

“Rain When I Die” is more expansive than the dizzying one-two punch of “Them Bones” and “Dam That River,” clocking in at over six minutes, the song takes its time building the atmosphere and mood. During the elongated intro, Mike Starr’s bass line takes centre stage as Cantrell’s wah-drenched guitar summons wicked banshee wails. Soon after the main riff hits like a tsunami, Cantrell’s expressive wah plays a central role. The song’s chorus is uplifting and crushingly beautiful.

Cantrell recalled writing “Rain When I Die” with Staley, “On that particular song, I had a really strong vocal idea and a cadence for the song, and so did he. He showed me his idea, and I showed him mine. And the weird part was where I had written lyrics, and places to sing were the spaces and the breaths in the song for him. So I’m like, ‘Dude, check it out. My line fits your gap, and your line fits my gap. Let’s put them together.’ We just combined them lyrically, and how well it worked was weird. We totally did not communicate what we were writing about, but it worked together. That’s one of my favourite songs on the record.”

“Down In A Hole” is the type of reflective “ballad” Alice In Chains thrived at. Calling the song a ballad is a stretch, but its slower pace and partially acoustic instrumentation set it apart from what came before. The song’s heaviness is existential; Layne sings, “Down in a hole, and I don’t know if I can be saved. See my heart, I decorate it like a grave. You don’t understand who they thought I was supposed to be. Look at me now: a man who won’t let himself be.”

“Sickman” opens with Sean Kinney’s tom-heavy beat, which rolls from speaker to speaker. Jerry’s riff is tight, understated and disorienting. The song’s verse descends into a nightmarish halftime dirge as Layne intones, “I can feel the wheel, but I can’t steer when my thoughts become my biggest fear. Ah, what’s the difference? I’ll die. In this sick world of mine.”

Cantrell recalls coming up with “Rooster” while staying with Chris Cornell and Susan Silver (manager of Alice in Chains and Soundgarden) at the couple’s apartment in West Seattle. “They were going to bed; I was working on music on my four-track all night, and when Susan got up at the crack of dawn, I played it, and she was touched by it.”

“My folks got divorced when I was pretty young, and I was the oldest of three,” Cantrell said of the roots of “Rooster,” “I didn’t spend much time with my pop during the teen years. I grew up with my Mother at my grandmother’s house, so we weren’t that tight, and he lived in another state, so I only saw him occasionally. And the song was a way for me to come to terms with that and maybe not judge him. I was trying to put myself in his shoes and maybe not judge him so harshly and try to understand his experience, which I think had a huge effect on his life and our family in retrospect.”

“Junkhead” is a look inside the early stages of an addicts’ mind. It kicks off a linked narrative that’s told on the second side of Dirt regarding drugs and addiction. That narrative has the songs protagonist falling in love with drugs as an alternative to normal life and then descending into the hell of addiction. “Junkhead” is the errant fool in the earliest stages of his fall. It’s not written as a glorification of addiction or heroin.

The album title track, “Dirt,” opens with an eastern-tinged guitar riff; Layne tracks the riff with a strident howl. The song settles into a mid-paced doom-laden grind; Jerry and Layne harmonise beautifully on the chorus, “One who doesn’t care is one who shouldn’t be; I’ve tried to hide myself from what is wrong for me.”

“Godsmack’s” riff is off-kilter and disorienting. Layne enters with a ghoulish, excessive vibrato before the chorus steadies the ship with beautifully harmonised vocals and powerful use of wah by Jerry. This yin/yang of dark and light carries on throughout. Jerry’s guitar solo is biting and dark.

“Iron Gland” is a forty-four-second interlude featuring Tom Araya of Slayer. An obvious reference to Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man.” “Iron Gland” shares the slowly depressed open string note “Iron Man” uses in its intro. At the end, someone is heard saying, “Redrum,” which is murder spelt backwards and a reference to the Stanley Kubrick movie The Shining.

The following two songs, “Hate To Feel” and “Angry Chair”, were brought to the band by Layne, who had recently started to play guitar and was becoming more confident writing on it. “Layne came into his own as a guitar player, and he wrote a couple of fantastic tunes on the guitar with ‘Hate to Feel’ and ‘Angry Chair,'” recalls Cantrell. “I love those tunes and the fact that he got the bug to pick up the guitar. I remember he showed us those tunes, and he was thinking about doing them for a record on his own. He was a big fan of Nine Inch Nails and Ministry and the whole industrial movement, and those were songs he pocketed for that. Then he played them for us, and we were all like, ‘Fuck, those are cool. We should do those.’ And he reluctantly agreed. And we cut them, and they turned out to be two amazing songs that very much fit the record, for sure.”

The album ends with “Would?” Jerry Cantrell’s ode to his friend, Mother Love Bone frontman Andrew Wood, after his death in March 1990. “We were hanging out with Cameron Crowe, and I knew he was working on a movie, and I knew Chris Cornell was working on some stuff for it, and the Pearl Jam guys were working on some stuff, and he was like, ‘I want you to write a song for this movie, man’,” Cantrell said. “I was thinking about Andy Wood; it was not long after Andy passed, and that was the genesis for the song.”

Vocally, Would? is an imposing back and forth between Cantrell’s eerie low-register delivery and late frontman Layne Staley’s anguished croon, and the guitarist says that it was Staley’s idea that Cantrell should take the lead vocal during the verse. Singles director Cameron Crowe also directed the accompanying video for Would?, which was released as a single in June 1992, and the band deemed the song too important to be a standalone track, “We ended up putting it on Dirt, even though it wasn’t recorded in the Dirt sessions, because it was such a strong song,” said Cantrell. “It sounds just a little bit different; if you listen to the rest of Dirt, those 11 songs have a bit of a different sound than Would?. It’s still one of our core tunes. It’s still so fun to play.”

Dirt is one of the era’s defining albums—a masterpiece in the truest sense of the word. It’s a look into the underbelly of the human condition and is unflinching in its report on the darker side of life. But there are shards of light throughout. The beauty of Dirt is in its ability to take the listener by the hand and guide them through the darkness. The band are our benevolent tour guides walking us safely through a nihilistic underworld. The journey is fascinating, life-affirming and visceral. It pummels the senses and leaves you craving another hit.

Cantrell talks about how Alice in Chains’ debut, “Facelift,” and “Dirt”, fit into the context of an era rich with dynamic rock records from fellow Seattle bands such as Soundgarden and Pearl Jam. “We might have all affected each other, connected to a cool movement, and one of the few times in my lifetime where it felt like the good guys were winning. ‘Dirt’ was a hell of a record. It stands the test of time and is a powerful piece of work without an ounce of fluff.” We agree, Jerry…!!

Essential…!