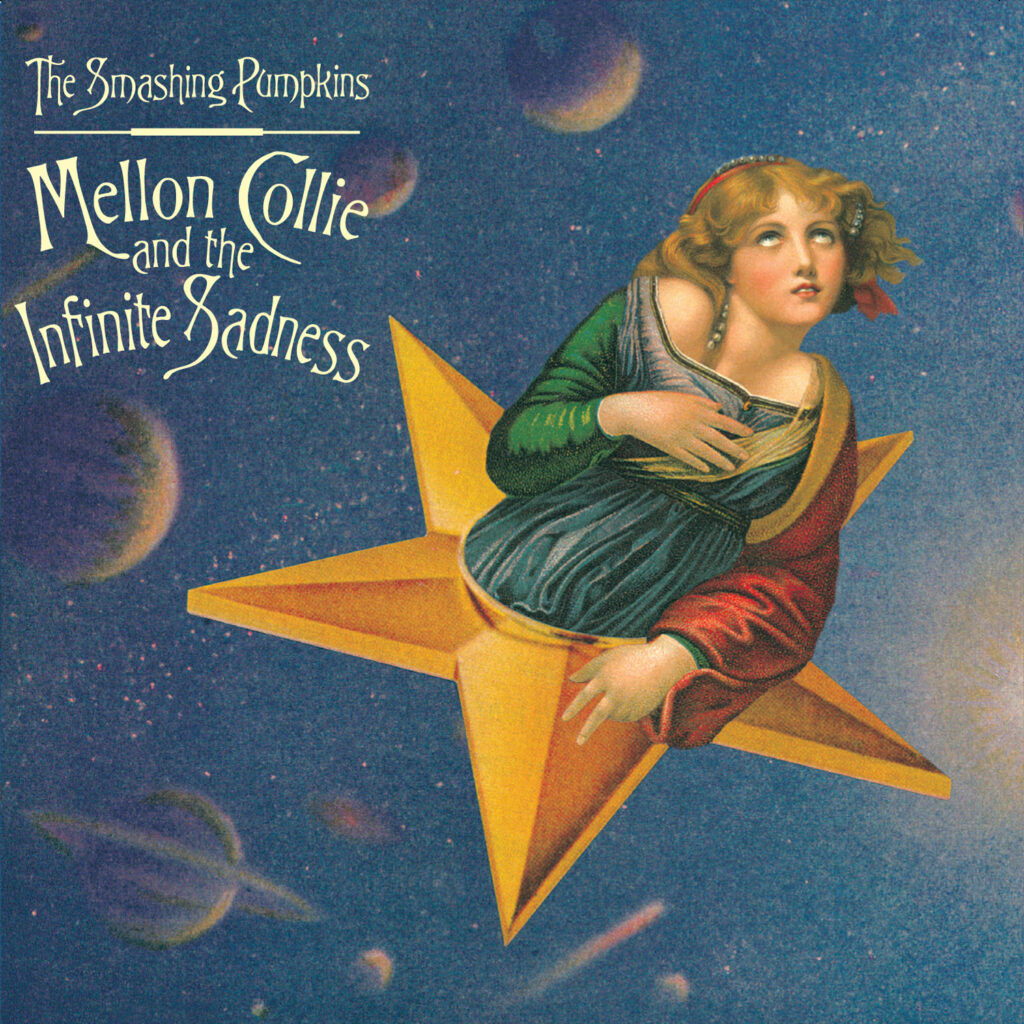

October 23rd, 1995, The Smashing Pumpkins released their third album, Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, through Virgin Records. By 1995, most of the bands that had ushered in the alternative rock boom of the early ’90s were in various states of turmoil. Pearl Jam was well into their retreat from the spotlight; Alice In Chains was in stasis, unable to tour due to frontman Layne Staley’s spiralling addiction, and Kurt Cobian had given up on life entirely. While their contemporaries contracted, The Smashing Pumpkins released a sprawling double album to rival the great double albums of the ’70s.

Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness is aeons deep, breathtakingly comprehensive, emotionally limitless and awe-inspiring in its scope. The twenty-eight-song tracklist was the only format that could contain the songwriting streak Billy Corgan was on at this time. The double album concept had become much maligned by the ’90s, with the odd notable exception since its ’70s heyday, most bands and record labels had given the idea of a double album a wide berth. The thought of presenting a band’s fans with such a sprawling conceptualization of their art was, by the ’90s, considered pretentious, unnecessarily bloated and only something those ageing rock dinosaurs partook in.

But there were precedents for greatness, even among the alternative rock subset. Throughout the 1980s, the bands that laid the foundations for the alternative rock house party of the ’90s dabbled with the double album formula. Hüsker Dü’s Zen Arcade, Minutemen’s Double Nickles On The Dime and Sonic Youth’s Daydream Nation are all searing examples of gifted talents pushing their creative convictions to the limit, with staggering results.

Whether Billy Corgan and company considered Physical Graffiti, The Wall, Quadrophenia or the Electric Ladylands of this world before undertaking the mammoth task of writing and recording Mellon Collie cannot be determined. One suspects it was more a case of the band, and Corgan in particular, being on such an inspired and voluminous creative streak that they had no reason to put the breaks on the outpouring due to the exceptionally high quality of the material.

To give some context of how mind-bendingly prolific The Smashing Pumpkins were at this time, let’s set aside the 28 tracks on Mellon Collie for a moment. One year later, in 1996, the band released The Aeroplane Flies High, a five-disc, thirty-three-song box set of songs written and recorded during the Mellon Collie sessions. Each of the five discs starts with a single from Mellon Collie, followed by a host of rarities recorded during the Mellon Collie sessions that didn’t make the final album.

Years later, this set was expanded to a ninty track deluxe edition. The Aeroplane Flies High is a cutting-room-floor companion piece to Mellon Collie that provides insight into Corgan’s extraordinary creative outbursts during this period of the band. And here’s the scary part: There is no filler. These supposedly second-string tracks are, for the most part, keepers and could easily sit alongside any tracks on Mellon Collie.

The songs on Mellon Collie set an incredibly high bar; it’s rock songwriting at its most potent, beguiling and impactful. To sustain that quality over twenty-eight songs is a herculean feat of artistry. When we consider the castaways presented on Aeroplain Flies High, which in many cases are as powerful as the album tracks, we get the picture of a band working on an entirely different level of creativity.

The Smashing Pumpkins were at the forefront of the alternative rock takeover in the early ’90s. They set their stall with the release of their debut album, the brilliant Gish, in 1991 and followed it up with the blistering masterpiece Siamese Dream in 1993. In 2020, Billy Corgan described the sea change in music culture that occurred at that time as: “One of those rare moments in time, like the 1960s when the counter-culture became the mainstream. And, it wasn’t neutered or weakened by the process. There are those rare moments when it pops through – and it’s shocking because it shouldn’t happen, but it did. We existed in that very sweet window where that was still possible. You could sing crazy songs about crazy things as loud as you could, and they were bigger than pop songs.”

This openness inspired many artists to take risks and trust their creative urges. The Smashing Pumpkins looked inward so they could push out; challenging self-examination and personal conflict had always been a part of their make-up, adding a splintered edge to their already fearsome attack, which in turn accentuated the beauty of their more sublime, dreamlike passage of music.

Billy Corgan’s controlling grip on the recording process of Siamese Dream meant he brazenly re-recorded complete sections of D’Arcy Wretzky and James Iha’s guitar and bass tracks. For Mellon Collie, he trusted more in his band’s talents, allowing them to play, and the results were better for it. Corgan’s reasoning for not trusting Iha and Wretzky’s abilities on Siamese Dream was not because they were incapable; rather, it was Corgan who was incapable of releasing control. Melon Collie shows that Smashing Pumpkins was a band of exceptionally gifted musicians in every department, and given the space to prove that, they resoundingly did.

Long before the release of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, Jimmy Chamberlin had marked himself out as one of the most gifted drummers of his generation. The ’90s coughed up some of the greatest rock drummers ever, and Chamberlin stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the best. James Iha’s guitar playing had proved integral to the band’s sound, painting beautiful counterpoint soundscapes while adding blistering lead work and crushing rhythm.

With Corgan re-recording sections of Iha’s and Wretzky’s parts on Siamese Dream, the rumour mill that followed found D’arcy Wretzky suffering most from insinuations and factual inaccuracies surrounding the situation. Corgan’s motivations for re-recording Iha and Wretzky’s contributions had little to do with their abilities as musicians. Instead, it had everything to do with the maniacal, perfectionist visions of a man in the fog of a severe nervous breakdown, trying to bring that album to fruition. While Iha suffered the same ignominy of having his parts re-recorded, he emerged unscathed. Wretzky took the brunt of false accusations regarding her abilities for years to come.

The truth is, for many, D’arcy Wretzky was the soul of the Smashing Pumpkins in the ’90s. Her sophisticated vocal harmonies beautifully elevated Corgan’s nasal howl to greater emotional heights, and her strident bass playing stood toe to toe with Jimmy Chamberlin’s powerhouse drumming night after night, not to mention her bewitching, magnetic stage presence, which added so much intrigue to the band. Nowhere was this more evident than on Mellon Collie and its subsequent tour.

Billy Corgan is a musical savant. Reliably iconoclastic and contrarian in equal measures, standing back to take in his staggering drive and breathtaking creativity during this period of the band is nothing short of astounding. Sure, he can’t have been easy to work with; visionaries like him rarely are. Corgan struggled with all his might to harness the enormity of Mellon Collie and mould it into a coherent package. “Mellon Collie is weird in that it’s a combination of nihilism, sentimentality and epic hope,” Corgan reflects. “That was where the generation was at that moment.”

Corgan has said the release was a fitting final opus for the group’s original lineup. “It was the last time the four of us worked together in earnest, and maybe I picked up on that; maybe I sensed that, and maybe that had something to do with the desperation and the approach to try and get as much as possible out of it.”

The band decided against working with Butch Vig, who had produced the group’s previous albums and selected Flood and Alan Moulder as coproducers. Corgan explained, “To be completely honest, I think it was a situation where we’d become so close to Butch that it started to work to our disadvantage. We had to force the situation sonically and take ourselves out of normal Pumpkin recording mode. I didn’t want to repeat past Pumpkin work.”

“Mellon Collie was a watershed moment,” reflects Corgan, “It was a convergence of a whole set of influences and feelings; it was right time, right place. You must be the right band at the right time to make a record like that. You can’t just flip a switch, and it happens. There was stability in the band; we had a great producer, and a lot of things came together.”

The songs on Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness are intended to work together conceptually, with the two halves of the album representing day and night. The CD and cassette versions of the album are divided into two discs, Dawn to Dusk and Twilight to Starlight. The vinyl version is divided into three records with six sides: Dawn/Tea Time, Dusk/Twilight, and Midnight/Starlight. The vinyl release also features two bonus songs, “Tonite Reprise” and “Infinite Sadness.”

The album spawned five singles. While Corgan considered issuing “Jellybelly” as the album’s first single, “Jellybelly was the song that I wanted to be the first single off of Mellon Collie,” Corgan said. “Right away, the record company was not having it. They wanted Bullet With Butterfly Wings. I put my foot down on this – ‘No, it’s going to be Jellybelly’. And the man from the label, Phil Quartararo, called me at home – I can still see myself standing in the kitchen. He said, ‘Kid – you’ve got to release Bullet first’. And I said, ‘OK, make your case’. He said, ‘Kid – it’s a smash!’ And I thought, this is one of those moments when I need to get out of the way! So Jellybelly never got released as a single, but I was convinced it was a single, and I’m still convinced it’s a single.”

“1979” was one of the last songs recorded for the album and was subject to a frantic overnight overhaul after producer Flood dismissed the original version he heard as “not good enough”. Once he listened to the improved version, it was immediately included on the album. Corgan had written the song from the perspective of his 12-year-old self when he was crossing from childhood into adolescence; in his own words, “a feeling of waiting for something to happen, and not being quite there yet, but it’s just around the corner”.

“1979” arrives gently with a skittering faded-in drum loop before the real drums kick in. It’s a dreamy pop masterpiece. Shot through with a hazy beauty, like a shard of evening sunlight on a blissful summer day. Its breezy optimism is charming and seductive. Corgan depiction of adolescent longing is palpable, “On a live wire right above the street, you and I should meet.”

The third single, “Zero”, opens with a darkly aggressive guitar hook. Corgan sings, “My reflection, dirty mirror; there’s no connection to myself, I’m your lover, I’m your zero, I’m the face in your dreams of glass.” There’s a baleful, venomous air to the entire atmosphere; the song’s mid-paced grind pulsates toward the memorable chorus of “Emptiness Is Loneliness, And Loneliness Is Cleanliness And Cleanliness Is Godliness, And God Is Empty Just Like Me.”

The fourth single, “Tonight, Tonight”, is epic in scope, driven by Billy Corgan’s urgently romantic lyrics, Jimmy Chamberlin’s stunning rolling drum patterns, and a thirty-piece string section pulled from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Being only the second track on the album, it marked a drastic change for the Pumpkins. Gish and Siamese Dream, although stellar, were more rooted in fuzzy rock guitars, blazing solos, and shoegaze dreamscapes. “Tonight, Tonight” was a cornerstone of the band’s expansion, showing off Corgan’s newfound, diverse musical tendencies.

The song’s enchanting music video almost never came to be. Directed by the husband-wife team of Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris (who went on to helm Little Miss Sunshine), the original concept was to have blankly smiling women in bathing caps performing elaborate swimming patterns and acrobatics. But Dayton and Faris had to revisit the drawing board when the Red Hot Chili Peppers released a nearly identical video for “Aeroplane”. They came up with a homage to classic French filmmaker Georges Melies and his milestone silent sci-fi film, 1902’s A Trip To The Moon.

The album’s final single, “Thirty-Three”, was described by Billy Corgan as “The first song I wrote when I got home from the Siamese Dream Tour. I used a drum machine, and the words just fell out.” Released in November 1996, “Thirty-Three” marked the band’s first release after drummer Jimmy Chamberlin’s firing.

Amid the lengthy world tour supporting the album, Chamberlin’s father died, and his substance abuse hit a fever pitch. Of this period, Chamberlin later said, “I learned that escapism was better than emotion, and that’s where I hid. It got to a point where I didn’t care. Life was scary for me.” At Madison Square Garden in New York City in July of 1996, Chamberlin and touring keyboardist Jonathan Melvoin overdosed on heroin; Melvoin subsequently died, and Chamberlin was ostensibly kicked out of the band to protect his health. Corgan later told MTV News that Chamberlin had overdosed twice during the Mellon Collie tour before the July 1996 event but that the band had managed to keep those situations private.

The singles only tell a small part of the story of Mellon Collie. Right throughout, the album is laced with incredible songs. The euphoric blast of “Jellybelly,” the floating, chugging cascades of “Here Is No Why,” the industrial undertones of “Love.” Beautiful pop masterpieces like “Muzzel” butt up against raging infernos like “Bodies.” Transcendental dreamscapes like “Porcelina Of The Cast Oceans” swell and breathe.

The possessed thrashing of “Tales Of A Scorched Earth” finds Billy shredding his vocal cords while the band shreds with maniacal rage. The gossamer beauty of “Stumbleine” is fragile and bewitching. “X.Y.U’s” passionate, hot-tempered assault starkly contrasts the theatrical whimsey of “We Only Come Out At Night.”

Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness is a masterpiece. It was the group’s most ambitious and accomplished work. Corgan presented himself as one of the last true believers: someone whose vision was far broader and deeper than the average ’90s rock star. In the making of Mellon Collie, he didn’t seem concerned with persistent alternative rock questions of ‘selling out’, and good for him: He was, and to this day, still is, aiming for something bigger and all-conquering.

What makes Mellon Collie genuinely spectacular is that the concept and scope of ambition are met with flawless material and execution. After the release, the band changed forever with the dissolving of the original lineup. That all-important chemistry was lost, and while they released a barrage of essential music post-Mellon Collie, the white-hot run of genius from Gish to Siamese Dream and into Mellon Collie will always stand as the band’s pièce de résistance.

Essential..!!