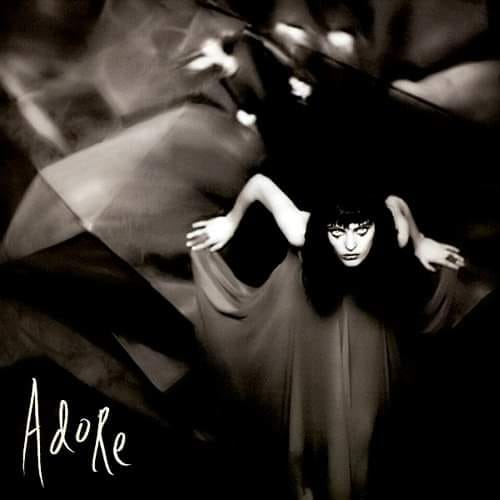

June 2nd, 1998, The Smashing Pumpkins released their fourth album, “Adore,” through Virgin Records. If common perceptions are to be believed, Adore is the Smashing Pumpkins album in which Billy Corgan and Co. alienated large swathes of the fanbase, embraced drum programming, added more synthesisers, dialled back the riffs, and adorned a goth look. While mostly true, the band still made an album as sprawling, confounding, and intriguing as Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness.

Left without a drummer after Jimmy Chamberlin’s dismissal, the Smashing Pumpkins took the opportunity to revamp their sound. Billy had already hinted at new directions even before Jimmy had been shown the door. After the enormous success of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, the band were on top of the world. However, rather than follow that success with a carbon copy, Adore is one of those “left turn” albums that follow a major mainstream success. The change in tone was partly by design and partly imposed upon them.

The Smashing Pumpkins have never been the most stable of units, but by June 1997, as they entered the studio to start recording, they were in dire straits. Billy would later characterise the situation as “a band falling apart”. They were coming to terms with the departure of Chamberlin and the fatal heroin overdose of touring keyboardist Jonathan Melvoin. Corgan was also going through a divorce and the death of his Mother.

How do you fill the enormous void left by the departure of a drummer of the calibre of Jimmy Chamberlin? In reality, the answer is you don’t. Instead of embarking on the monumental task of finding a replacement, the band used three-session drummers and embraced the stoic creativity of drum machines. Session drummer Matt Walker played on seven of the album’s songs. Fellow session ace Joey Waronker drummed on two songs, with Soundgarden’s Matt Cameron playing on the song “For Martha.”

The use of a drum machine harked back to the band’s earliest incarnation. Before Jimmy Chamberlin joined in the late ’80s, The Smashing Pumpkins gigged and recorded with a digital timekeeper, so the drum machine concept was familiar to the band.

References to Corgan’s Mother’s death are present throughout, but the album is rather striking in its calmness. The bombast and thrilling, distorted power of previous albums are largely missing. At times, Billy sounds almost at peace, even amid such personal strife. The atmosphere is, at times, hushed and haunting, with occasional dalliances toward the more hard-rocking side of the band’s sound.

The weeks after Adore’s release, the album was met with lukewarm reviews and sluggish sales. For those who never quite took to Corgan’s personality, the new record became a renewed excuse to criticise the band’s primary songwriter. “The lyrics are generally on the wrong side of the line between deeply personal and deeply meaningless,” Douglas Wolk wrote in Spin. In a review for Rolling Stone, Greg Kot, an early champion of the band, suggested that Adore was “a weird little album that turns its back on the band’s previous strengths and shrinks the Pumpkins’ sound.” While Kot was dismissive in his remark, he hit upon the core reason why the record did not replicate the sales success of Mellon Collie: it did not replicate its sound.

The baggage of “Melon Collie” hangs over Adore. It would always be unfairly thought of simply because it happens to be the follow-up to a world-conquering behemoth. But taken on its terms, Adore has an awful lot to like. Corgan blamed himself for the record’s reception with the public, saying he “made the mistake of telling people it was a techno record” and that if he “would have told everyone Adore was the Pumpkins’ acoustic album, we would have never had the problems that we had”.

Billy wrote on the band’s website that the album’s title was “misunderstood” and “a joke that no one ever got.” He explained that Adore was meant as a play on “A Door,” meaning the album would offer a new entrance to the band’s career. In 2005, he called the making of the album “one of the most painful experiences of my life.”

Only Billy Corgan would consider a 74-minute, 16-track album a modest effort. Still, compared to its widescreen predecessors, Adore feels more mid-paced and sombre, with less dynamic peaks and valleys of the searing Siamese Dream or Mellon Collie. Each song is as strong as any Pumpkins offering to date. There’s a beautiful, meditative atmosphere to this album. Some might miss the thrilling dynamics that permeated their earlier albums.

Gish, Siamese Dream and Melon Collie balanced hard-hitting riffs with meditative ballads and exciting experiments. That formula had been de rigueur for the band and catnip for the fanbase up until Adore. Those who left their expectations and baggage at the door when listening to Adore are more likely to see the album’s charm and beauty.

Adore is arguably better than most of the Pumpkins’ albums that came after. But in 1998, that wasn’t quite enough. The album is certainly misunderstood—a sidestep after an avalanche of success. It’s hard to know how it would have been perceived had it been a stand-alone release, out of the shadow of Melon Collie and the drama that surrounded its birth.

Opening the album is the stunningly beautiful “To Sheila,” undoubtedly one of the most heartfelt and fragile pieces of music the band committed to tape. Corgan’s voice is naked and impossibly present as if delivering each word over your shoulder directly to your ear. Atmospherics swell and dip as piano, guitar, banjos and affected percussion weave between the waves. D’Arcy Wretsky’s backing vocals are breathtakingly realised and delivered with divine precision.

“Ave Adore” picks up the pace with a galvanising industrial beat. Glitchy and rough-hewn, Corgan sings over the machine-like din, “It’s you that I adore / You’ll always be my whore / You’ll be a mother to my child / And a child to my heart / We must never be apart.” Despite its dark edge, the song bristles with memorable hooks.

“Perfect” shares the same feel and tone as the Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness’s hit “1979.” It feels like a sister song, sharing similar instrumentation and vocal delivery from Corgan. But it stands on its own as a slightly more melancholy flipside to the joyous outpouring of “1979.”

“Daphne Descends” feels cinematic; it strives for something grandiose but is tethered by a gnawing sadness that seeps through the entire track. It’s a gorgeously orchestrated rock song that broadens the Pumpkin’s sound with flourishes of electronica meshing with the widescreen guitars.

“Once Upon A Time” flows with a shuffling whimsey. It’s a bewitching acoustic number that glides and swoops through a rich tapestry of atmospheric instrumentation. While the subject references the death of his Mother, the tone is celebratory and strives to honour her life as Billy sings, “Mother I’m tired / Come surrender my son / Time has ravaged on my soul / No plans to leave, but still I go.” The song’s outro builds in rapture as Billy heartbreaking intones, “Mother, I hope you know /

That I miss you so / Time has ravaged my soul / To wipe a mother’s tears grown cold.”

“Tear” opens with crashing percussion and lavish strings before dropping to an understated verse. Billy sings over nothing more than a drum machine’s throbbing, upper-register beat before the grandiose, crashing percussion and strings return. There’s a spaghetti western tinge to the track’s mood as if the band is soundtracking a modern-day Sergio Leone movie.

“Crestfallen” is a beautifully dour piece built from rolling keys and an understated drum machine pattern. “Apples + Oranges” is gripping and strident, resembling something The Cure’s Robert Smith may have dreamed up if he was writing for The Smashing Pumpkins. The song’s electronic elements become more pronounced as its journey unfolds. Considering where the Pumpkins came from, it’s a brave and primarily successful left turn.

“Pug” again ups the ante and pushes the electronic elements to the fore. The guitar counterpoints offer a sinister feel to the verse while they lighten the tone during the song’s chorus. “The Tale Of Dusty And Pistol Pete” is a gripping story about Pistol Pete, who murders Dusty. He thinks he has gotten rid of her, but she comes back and haunts him, unaware that she is a ghost. The instrumentation is warm and acoustic, shot through with shards of evocative electric guitar.

“Annie-Dog” opens with a meditative piano playing an ascending row of block chords. Billy sings above the odd intervals; Matt Walker’s drumming is perfectly weighted and often jazz-like, matching the swinging feel of the piano attack. “Shame” continues with a meditative feel but employs a very different atmosphere. A plain drum beat, heavy on the ride cymbal anchors throughout as waves of e-bowed guitars sweep across the droning mass of washed-out atmospherics.

“Behold! The Nightmare” seethes and gushes with a warped undercurrent of electronica. Mid-paced and pensive, the song lifts during its chorus, and D’arcy again adds significantly with her pitch-perfect backing vocals. At the two-minute mark, the song takes a significant turn, reverting to a single acoustic guitar playing some beautifully off-beat folk passages and stunningly orchestrated backing vocals before returning to the sea of atmospheric electronica.

The beautiful piano ballad “For Martha” is a tribute to Billy Corgan’s Mother, Martha Corgan, who died of cancer in 1996. Billy said of the song, “It’s a seven-minute or so opus with lots of parts, stops and starts, and even tempo change. I played the piano live in an “isolated” room while James and D’arcy were on the floor in the main room. We did many takes to get the whole piece just right, and it turned out beautifully as everyone played with a lot of passion and soul. It’s a real highlight of the record.”

“Blank Page” is another piano dirge that benefits from arching strings; these passages act as relief, punctuating the solemn nature of the piece with monochromatic light stabs. The album closes with “17.” The piece consists of eighteen seconds of a distant mournful piano, which abruptly ends mid-passage.

Say what you will about Billy Corgan and The Smashing Pumpkins. They are a brave band; they single-mindedly follow their muse. They take enormous risks commercially and creatively. Probably more so than any other band of their generation. Adore is a beautiful album. One that feels like the logical conclusion to the ’90s arc of the Pumpkins story, which started in 1991 with Gish, continued with the heady rocket ship blast of Siamese Dream and Melon Collie and ended with the atmospheric drift back to earth with Adore in 1998.

Listening to the album today, removed from the trappings of expectation and the prevailing cultural wants, Adore feels like a triumph. Taken on its terms, it’s a grand-scale epic that doesn’t use bombast to prove its grandiose weight; instead, it’s a cinematic reflection on the fragility of life itself. It’s an all-important piece of The Pumpkins catalogue.

Essential..!